In a busy health facility in Western Zambia, Registered Nurse Akalilwa Akalilwa noticed a pattern that troubled him—children eligible for but missing critical vaccines, women with human papillomavirus (HPV) cases without cervical cancer screenings, or clients with Tuberculosis (TB) symptoms leaving the clinic without screening for the disease.

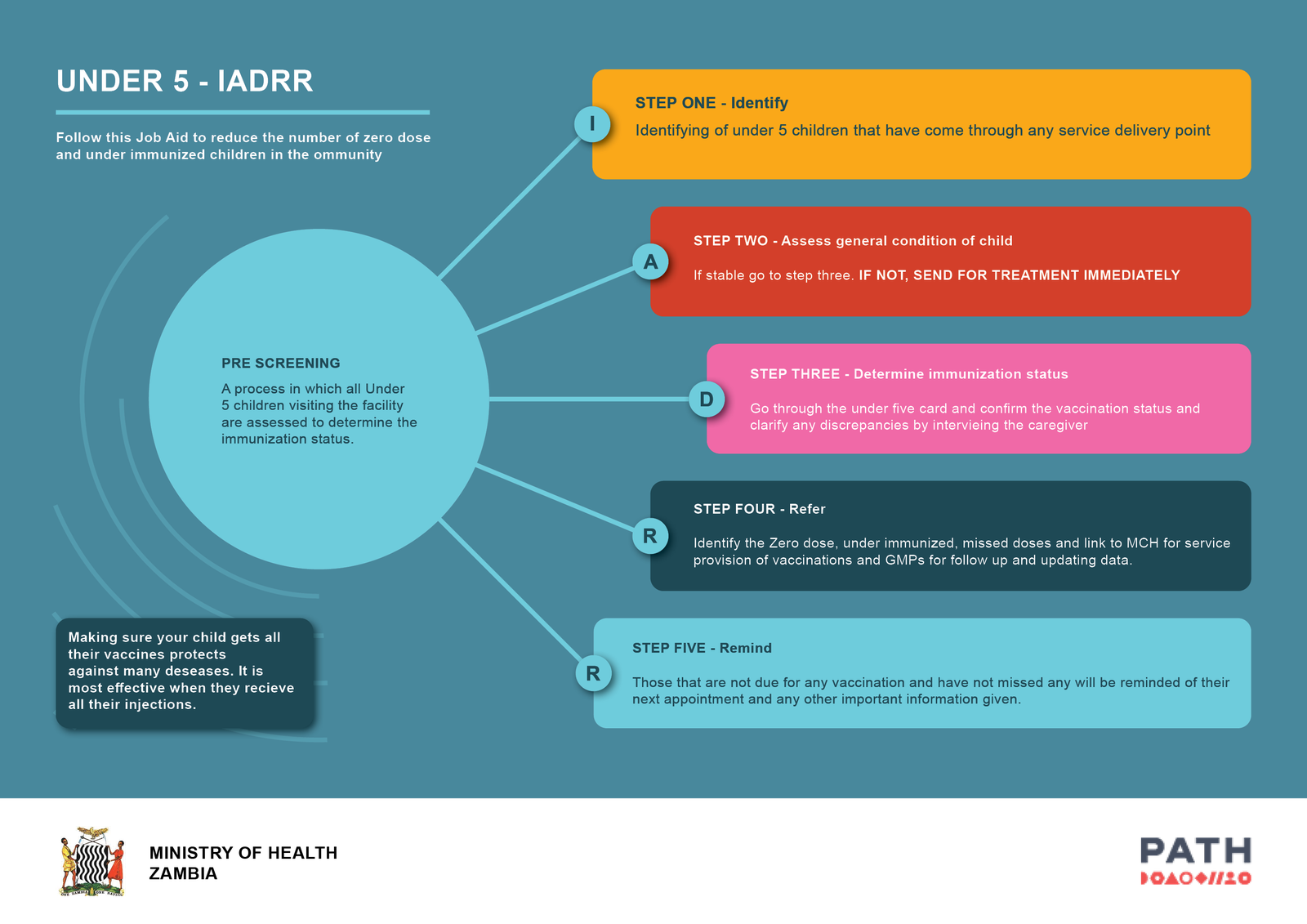

That observation sparked a solution, developed in partnership with PATH’s Living Labs team: the Identify, Access, Determine, Refer and Remind (IADRR) job aid.

We sat down with Nurse Akalilwa to hear how this idea came to life, and what it’s meant for him, his clients, and the broader health system.

Q: What challenge were you trying to solve with the IADRR approach?

Akalilwa: I’m a Registered Nurse working in a facility where I often saw children come in for services such as outpatient care for acute illnesses but they were not being referred to other departments like Maternal and Child Health, where additional needs could be addressed. As a result, many left without receiving the vaccines they were eligible for.

During a Living Labs workshop in Kabwe, we were grouped with colleagues from other provinces and asked to address real problems in our facilities. For us, the scenario was the large number of children missing their 9-month measles vaccine. That’s how the idea for IADRR was born—to create a simple, user-friendly job aid to identify and track these children wherever they enter the facility.

Defaulters and zero-dose children were the primary concern, but we also saw similar challenges with adult clients, especially with cervical cancer screenings. Many women didn’t come forward because they didn’t feel sick or were uncomfortable with the screening process.

By integrating IADRR into our workflow, we could identify eligible women early. Within just three months, we saw a major increase in screenings. The job aid also helped us catch pediatric TB cases that would have otherwise been missing. Through the job aid, we identified five children in our district, in fact.

One child was losing weight and coughing, which was initially blamed on dust or poor nutrition. But through IADRR, we screened and diagnosed both the child and his father with TB.

Q: How did you introduce IADRR into health care visits, and what results have you seen?

Akalilwa: At first, some patients saw it as a delay. For example, if we were isolating women aged 18 to 49 for cervical cancer screening, there was some hesitation. But with time and sensitization, acceptance grew. We started using it right at the triage point to ensure no one slipped through the cracks.

There are real stories that show the job aid’s value. One woman, very resistant to screening, was later diagnosed with cervical cancer. Thanks to early detection, she was referred for treatment. Without IADRR, she might not be with us today. The same with TB. We identified children who were symptomatic but overlooked.

The approach has reduced the number of missed doses and helped us catch issues earlier. That not only improves client outcomes but also reduces the cost and burden of follow-up. Our district TB coordinator was impressed and asked about our strategies. I’ve even trained other facilities in using IADRR and it’s now being used in communities and schools, asking, “Have you ever been screened for TB?” at other touchpoints of health care delivery.

As we move toward electronic health records, job aids like IADRR help bridge gaps. The digital systems are not yet fully adopted, and many staff find them challenging. But IADRR works in the here and now, even as we transition.

Q: How did human-centered design (HCD) shape this project?

Akalilwa: It was empowering. The idea came from us, the users, and that meant the solution was realistic and grounded in the day-to-day issues we face. Instead of being handed a tool, we were part of its creation. That made all the difference.

The motivation it brings is what stands out to me. In many projects, people start strong, then drop off after a few weeks. But with IADRR, users are seeing results—they’re uncovering hidden issues, and that keeps them going.

Living Labs has been very innovative, and I’d love to see this model and job aid scaled to more places.

Human-centered approaches to care

Health workers like Akalilwa often work in under-resourced settings with limited staff and high demands. Job aids like IADRR don’t just help catch what’s missed, they boost morale, improve clinical performance, and save lives.

As Zambia and other countries work toward improving immunization and screening rates, this user-led, human-centered approach could be the key to unlocking better health outcomes for all.