Nearly all cervical cancer cases—more than 95 percent—can be attributed to HPV infection. Vaccinating adolescent girls against HPV is one of the most effective ways to prevent cervical cancer from occurring when they reach adulthood.

More than 150 countries have national HPV vaccination programs, and many are primarily centered around schools, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). These strategies efficiently reach the majority of adolescent girls, but it means that girls not attending school are frequently missed during HPV vaccination campaigns.

In recognition of World Cervical Cancer Elimination Day today, PATH is sharing new results from a qualitative study about strategies for reaching out-of-school (OOS) girls with HPV vaccination in LMICs. On behalf of the HPV Vaccine Acceleration Program Partners Initiative (HAPPI) Consortium, PATH conducted interviews with a range of stakeholders in seven LMICs to identify innovative strategies, challenges, and opportunities to vaccinate OOS girls against HPV.

The HAPPI Consortium, which is managed by JSI with the Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI), the International Vaccine Access Center (IVAC) at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Jhpiego, and PATH as partners, is working to accelerate adoption of sustainable and successful HPV vaccination programs in LMICs. Understanding implementation strategies for reaching OOS girls with HPV vaccination will help to identify effective interventions that LMICs can implement to increase uptake in population groups less likely to be vaccinated.

Where OOS girls are found

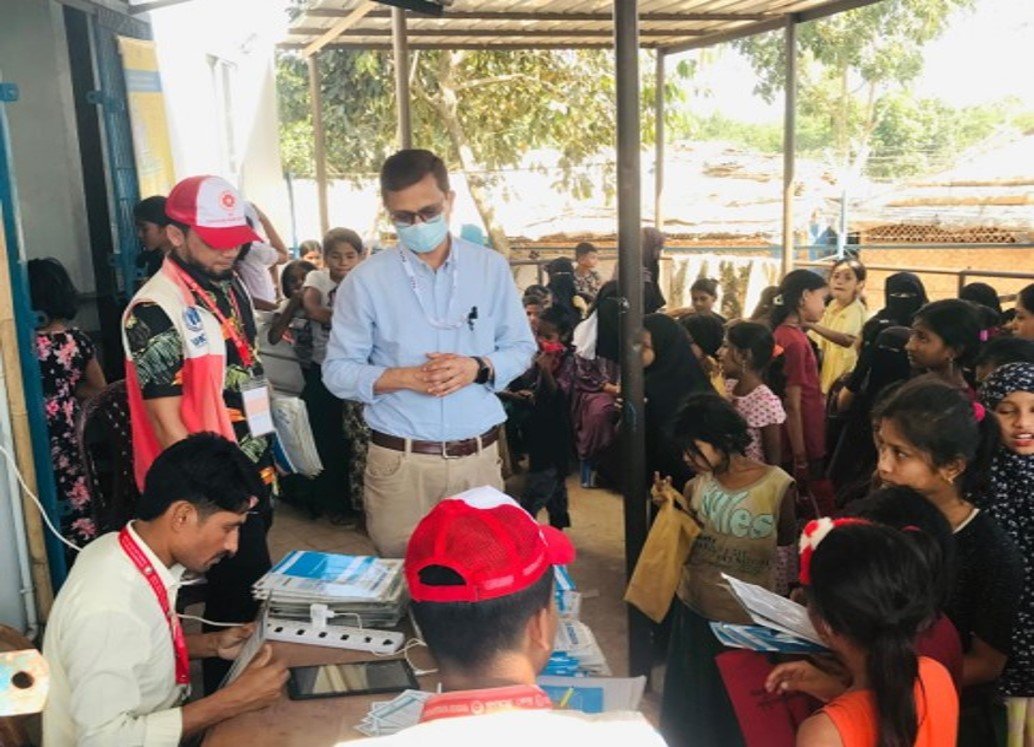

Between December 2024 and May 2025, PATH conducted 77 interviews with national and subnational stakeholders in Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, The Gambia, Mali, Senegal, and Solomon Islands to identify innovative strategies for vaccinating OOS girls. The stakeholders included vaccinators, community health workers, policymakers, special advisors, health facility managers, and community leaders.

“The interviews explored archetypes of OOS girls and where they are located, along with strategies for enumeration, planning, and service delivery for reaching OOS girls with HPV vaccination,” explained Jessica Mooney, Deputy Director of HPV Vaccine Implementation Programs at PATH’s Center for Vaccine Innovation and Access (CVIA) and one of the study leads. “We found that many of the OOS girls in these countries were living in marginalized settings, ranging from rural villages and urban slums to migrant or informal settlement communities.”

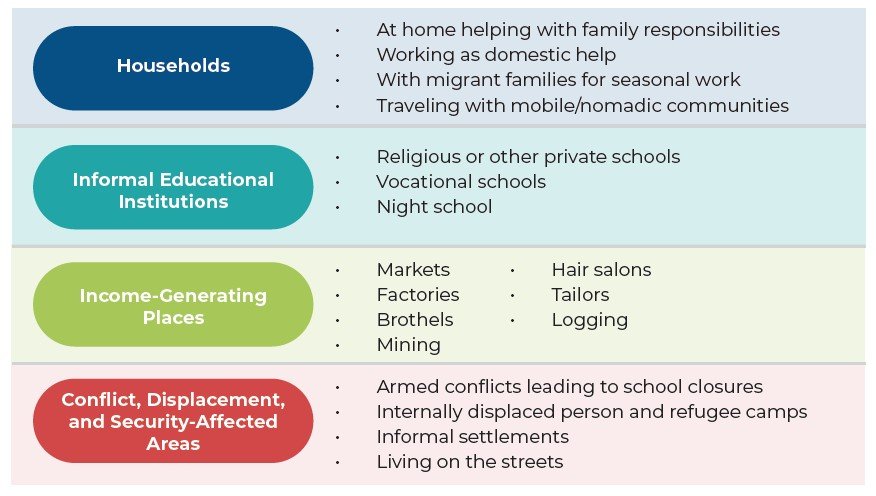

This figure summarizes where OOS girls are located in the study countries, providing helpful context for determining strategies for reaching them with HPV vaccination.

Many of the OOS girls in the study countries are engaged in income-generating work such as domestic labor, market vending, or agricultural and industrial jobs, with some exposed to exploitation. Their exclusion from formal education stems from a mix of socioeconomic and cultural barriers, including gender-biased family priorities, lack of civil documentation, early marriage, limited school infrastructure, and family concerns about education quality.

One challenge many countries face is that there is no centralized list to identify OOS girls, as governments or institutions do not typically gather this information. Effective planning requires mapping where these girls live and understanding the factors that influence their mobility and care-seeking behavior.

Innovative approaches to HPV vaccination

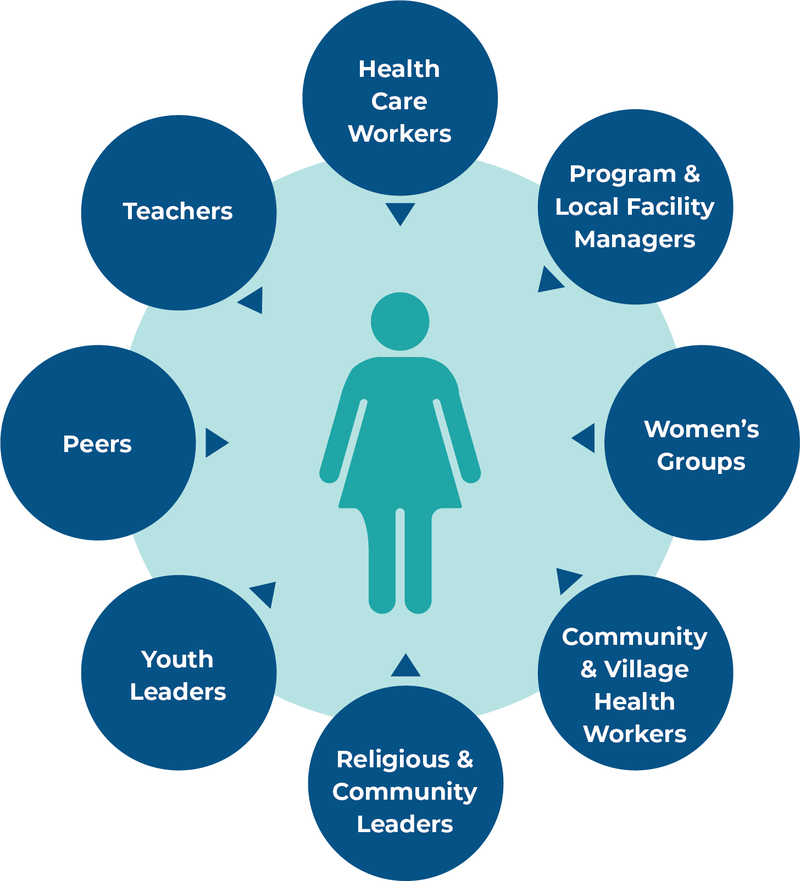

Other key findings from the study include learning that engaging a diverse range of stakeholders early in HPV vaccination planning, providing community and village health workers with incentives for their outreach efforts, and using varied outreach and service delivery platforms can help get more OOS girls vaccinated.

For countries switching to a single-dose HPV vaccination schedule, operational efficiencies—such as reduced vaccine and delivery costs, less staff time needed for follow-up doses, and more flexible outreach strategies—have enabled health systems to reallocate resources toward intensified efforts to reach OOS girls.

This figure depicts the diverse types of key stakeholders identified in the study countries who are needed to reach OOS girls with HPV vaccination.

Country-specific findings from the study also provide helpful insights into how they currently engage with OOS girls, as well as an opportunity for sharing lessons learned about strategies that may be useful for other countries in the same region or that may be facing similar challenges.

“In Bangladesh, for example, health care workers conducted house-to-house visits to identify and register eligible OOS girls, followed by microplanning and interpersonal communication efforts to inform and engage the girls and their guardians about the HPV vaccination schedule,” said Dr. Muhibul Kashem, Senior Program Officer at PATH and the study lead in Bangladesh.

In many of the study countries, building trust through religious leaders, elders, and women’s groups is vital to gain entry into households and closed or mobile communities where OOS girls live. It’s also important to remember that country context can vary, rather than assuming a blanket approach will work the same everywhere.

“In pastoralist areas in Ethiopia, mobile support teams are used to identify and vaccinate OOS girls. However, in conflict-affected areas, a ‘hit and run’ strategy is used to quickly mobilize and vaccinate eligible girls,” shared Diriba Bedada, Project Director, Vaccine and Immunization Programs at PATH Ethiopia and the study lead there.

Leveraging shifting resources

In tandem with the OOS girls study, PATH conducted a similar qualitative study with 35 stakeholders in Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, and Solomon Islands to obtain insights into how switching to a single-dose schedule has impacted HPV vaccination programs in LMICs.

Results across all three countries were strongly aligned. Common findings emerged related to improvements in HPV vaccination coverage, reduced vaccination and delivery costs, more efficient service delivery logistics, and enhanced program sustainability, all thanks to the switch to a single-dose schedule. These shifts can help countries reinvest in community outreach, enumeration, and engagement strategies tailored to OOS and other hard-to-reach girls, thereby strengthening long-term HPV vaccination equity and coverage.

Taken together, PATH and the HAPPI Consortium hope these two studies can help fill critical knowledge gaps about how to successfully reach OOS girls with HPV vaccination. Ensuring equitable access to HPV vaccination, especially in LMICs, can help move the world closer to eliminating cervical cancer for good.