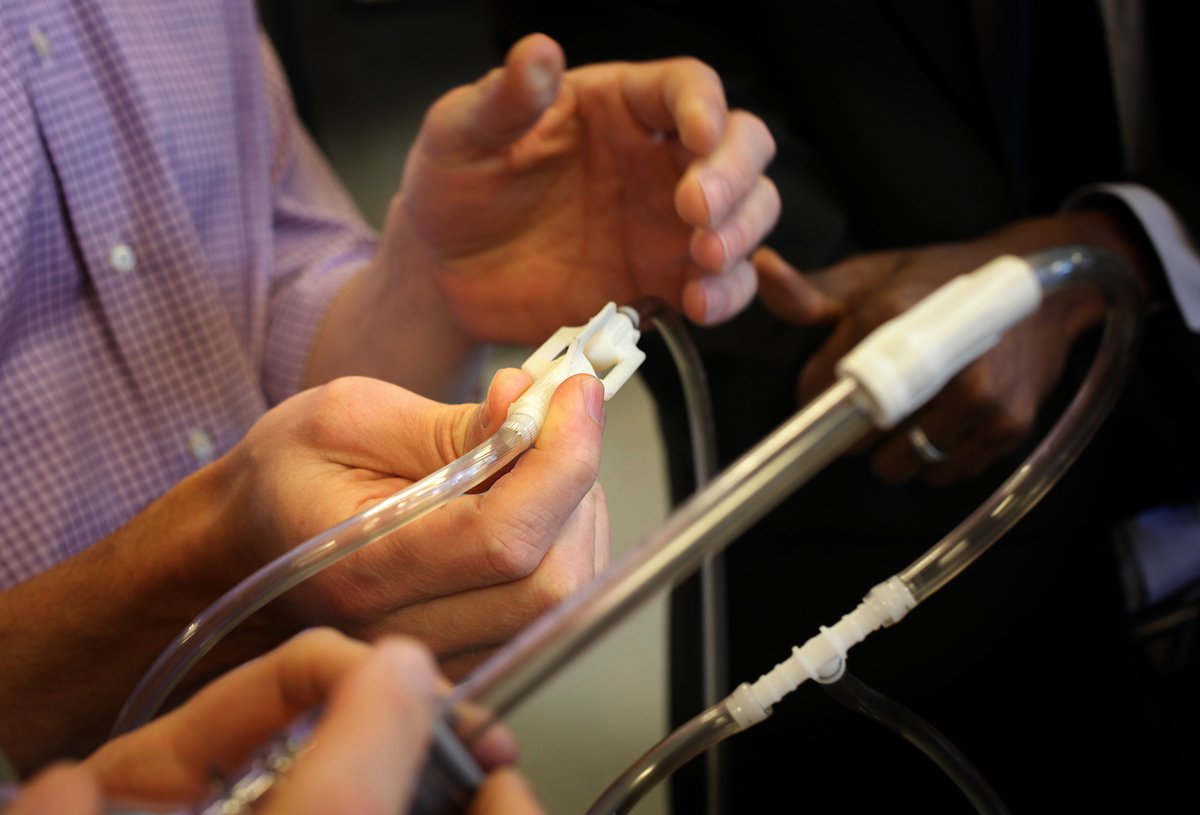

When experts gather around the prototypes of lifesaving devices in the PATH shop, it never takes long for questions, opinions, and stories to start flowing.

This week, the devices in question were a low-cost bubble continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) kit and an oxygen blender. We have been collaboratively developing these technologies with partners from University of Washington Department of Pediatrics, Seattle Children’s Hospital, Adara Group, and Kiwoko Hospital for use in health facilities with limited resources. And the experts who gathered from PATH and those partners represented diverse fields: neonatal medicine, medical product engineering, commercialization, and public health.

There is a clear need for these devices: respiratory infections are a leading cause of infant mortality in many of the world’s poorest places and claim millions of newborn lives each year. A bubble CPAP device can provide an infant with the air pressure needed to support their breathing, and when combined with an oxygen blender, it can deliver critically needed oxygen at appropriate concentrations. These interventions can mean the difference between life and death, and between healthy infant development and lifelong neurological damage or blindness.

How can we ensure that every baby, no matter where he or she is born, has an equal shot at a healthy, productive life? Photo: PATH/Gabe Bienczynski.

While bubble CPAP devices and oxygen blenders are standard in American neonatal wards, their high cost puts them beyond the reach of many hospitals, as does their requirement for pressurized oxygen and air, steady power, and access to trained technicians and replacement parts.

PATH and our partners have been working to refine the design for an oxygen blender and an ingenious, low-cost bubble CPAP that is made primarily from common medical supplies kept in stock by most medical equipment vendors in the developing world.

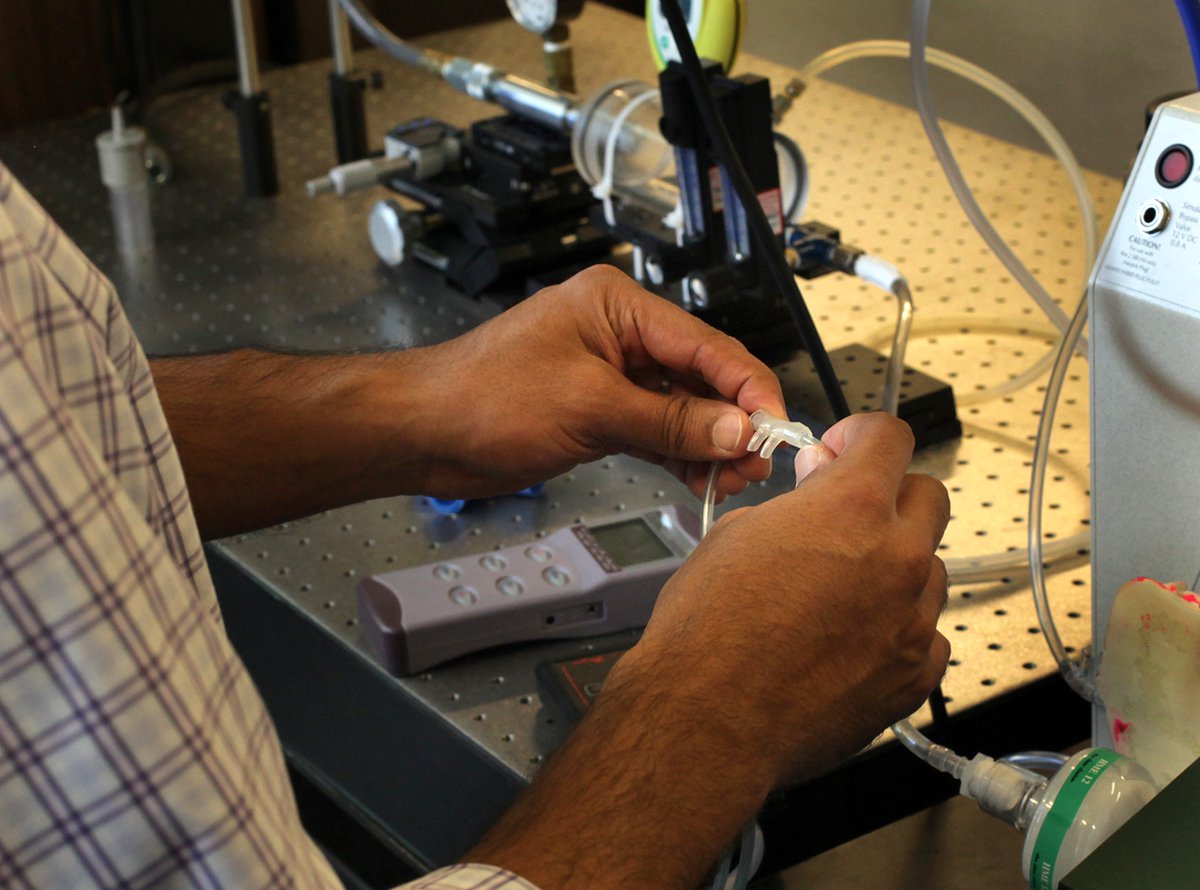

PATH is developing an inexpensive oxygen blender that mixes air and oxygen in specific concentrations, and can be used when administration of 100% oxygen is not appropriate. Photo: PATH/Tom Furtwangler.

The inspiration for these devices came, as it often does, from stories of newborn lives that had been saved with improvised, cobbled-together bubble CPAP solutions built by clinicians who were short on resources and long on ingenuity. Those handmade devices worked in some settings and situations, but they had not been rigorously tested, were difficult to scale up, and sometimes relied on the presence of their designer for effective use.

In the PATH shop, experts from a variety of disciplines contributed to a wide-ranging discussion about how to develop a device that is inexpensive, easily maintained, and meets the needs of clinicians. Photo: PATH/Tom Furtwangler.

Funding from the Saving Lives At Birth Grand Challenge and other supporters is allowing refinement of these concepts into manufacturer-ready designs suitable for widespread distribution.

But there are many hurdles to getting inexpensive, high-quality devices designed, manufactured, and commercially available in the settings that need them. So in the shop, as experts from each discipline contributed to the conversation, the design decisions and trade-offs became sharper, while the list of issues and considerations grew longer.

Can hospital staff be trained to disinfect and reassemble, or should some parts be single-use and disposable? Is there a manufacturer in Africa who can make precision parts at low cost, or will they need to be imported? Is it more important to make a simple device that is effective in the most critical situations, or a more complex, adjustable device that is effective in a wider range of situations and environments?

Part of the product design process includes running low-cost parts through highly sensitive tests designed to mimic real world conditions. PATH shop technician Alec Wollen shows how it’s done. Photo: PATH/Tom Furtwangler.

Passing around a variety of tube-and-bottle bubbler combinations as they worked through the lunch hour, the group nailed down dates for an upcoming round of user input at a Ugandan hospital and planned site visits to African device manufacturers. And then after breaking for just a few minutes, the group began considering the next design perspective, as a commercialization expert presented a comprehensive overview of the market for bubble CPAP devices in India.

Designing for very small infants and for the very big picture

This cross-disciplinary process embodies many of PATH’s unique and distinctive competencies. Focusing a broad group of experts on the challenge of saving the largest number of newborn lives possible, the project asks them to consider the design of neonatal respiratory devices from every angle, to learn from each other, to try hands-on experimentation, and to think holistically. Having advanced hundreds of projects over four decades, PATH brings our own experience to the table as a convening partner.

In order to design an effective and sustainable solution, a wide range of factors are considered: from the width of premature newborns’ nostrils to the World Health Organization’s policies. Photo: PATH/Tom Furtwangler.

The design thinking encompasses the whole system in which the device will be manufactured, approved, marketed, used, and maintained. The conversation ranges with equal emphasis from the shape of tubes that will fit comfortably into a premature baby’s nose, to the complexities of manufacturing, assembly, and supply chains, to the relevant World Health Organization policies.

Detailed charts and graphs are presented. Stories are told. The group names other experts they should consult, lists manufacturing partners to consider, and brainstorms questions to ask in Africa when gathering additional stakeholder feedback on the prototypes.

But no matter how technical the discussion gets, nobody forgets why they are here. “When you follow up, and a baby has passed away,” says Ugandan colleague Dr. James Nyonyintono, who traveled to Seattle for this work, “you ask yourself: what could I have done differently?”

This post originally appeared in Mapping the Journey, a multi-part series exploring how PATH turns ideas into solutions that bring equity, dignity, and health to women, children, and families worldwide.

PATH’s partners on this project include Adara Group, Kiwoko Hospital Uganda, the University of Washington Department of Pediatrics, and Seattle Children’s Hospital. This project is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of PATH and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.