A story behind the statistics

“I was so sad, shy, and depressed. Suicide was the only thought when I found out that my baby was born with only one arm.”— Ma Nyo, 37 years old

After losing twins at five months pregnant, Ma Nyo (name changed) clung to hope during her next pregnancy, only to face another heartbreak. Her newborn daughter's congenital absence of a forearm sent her into a spiral of shame and withdrawal.

“I hid at home, starving myself until my breast milk disappeared,” the 37-year-old recalls. Her daughter's worsening malnutrition became a visible measure of her invisible suffering: a cycle of grief, stigma, and deteriorating mental health repeating across Myanmar's villages.

Her story reflects a brutal truth: in contexts where health care resources are stretched thin, perinatal mental health (PMH) conditions don't exist in isolation. They amplify maternal mortality, child malnutrition, and intergenerational poverty, and yet remain buried under silence.

Ma Nyo and her baby were ultimately saved through a coordinated web of care: a community midwife who recognized both the baby’s faltering growth and the mother’s distress; culturally adapted counseling that addressed trauma alongside practical breastfeeding struggles; and neighbors who gradually became allies rather than judges. Yet for every mother like Ma Nyo, struggling with her own unique distress, there are countless others who suffer unseen—their mental health needs overlooked at every stage of the maternal journey.

This dual focus on clinical competence and community trust is where systemic change begins. When health workers can spot PMH needs as readily as anemia and when villages view mental health support as routine as prenatal vitamins, resilience replaces ruin.

A service provider providing mental health support to a mother using a PMH flip chart. Photo: PATH.

The path forward: integrating PMH care

Addressing issues like this require more than isolated interventions. They demand collective solutions and a sustained commitment to integrate mental health support into the fabric of maternal care.

Progress hinges on two foundations aligned with the local context: strengthening health systems to reliably identify and address PMH needs, and fostering environments in which women and families can seek support without stigma.

These steps are not merely beneficial but essential for child development, family stability, and community resilience. In Myanmar’s complex landscape, achieving such systemic change is both an urgent priority and a challenging goal—one that is possible only if efforts remain rooted in local realities and coordinated across all levels of care.

“To translate these foundations into action—strengthening systems and reducing stigma—a critical tool was needed to integrate into all maternal health care implementation.”— Dr. Thida Lin, Programs Director, PATH Myanmar

Recognizing this critical gap, a milestone was achieved through the Perinatal Mental Health Manual for Health Care Providers in Myanmar—a collaborative effort between the World Health Organization (WHO) Myanmar, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Myanmar, and PATH.

Developed with funding from UNICEF, technical guidance from WHO and UNICEF Myanmar, and expertise from PATH staff and mental health practitioners, the manual bridges global evidence with Myanmar-specific contextual knowledge, creating a culturally relevant resource.

PMH IEC materials including poster, pamphlet, flipchart and guidebook presenting in a training. Photo: PATH/Phyo Wai Lynn.

A locally adapted roadmap for maternal mental health

The PMH training package, which includes a training guide book and other related job-aids such as a flip chart, pamphlet, poster, and presentation deck, is intended to be a useful and trusted companion for all dedicated maternal and child health (MCH) care providers across the country on a daily basis.

It is grounded in the WHO’s Guide for the Integration of Perinatal Mental Health into Maternal and Child Health Services, which provides a framework for integrating mental health care into routine services delivered by non-specialist health care providers.

Adapted to the Myanmar context, this package equips frontline health care providers—including health volunteers, midwives, nurses, and general practitioners—with practical tools and guidance to identify, assess, and respond to PMH conditions. It promotes early detection and intervention through routine contacts within MCH services, and emphasizes person-centered, culturally sensitive, and trauma-informed care.

The manual also highlights referral pathways and coordination mechanisms within the health system to ensure women receive timely and appropriate support.

“What makes this manual unique is how it translates WHO’s global standards into actionable steps for Myanmar’s frontline health workers—from early identification and managing mild to moderate cases and referring the severe ones—that actually function in local contexts,” said Dr. Kyi, a mental health expert.

“What makes this manual unique is how it translates WHO’s global standards into actionable steps for Myanmar’s frontline health workers.”— Dr. Kyi, mental health expert

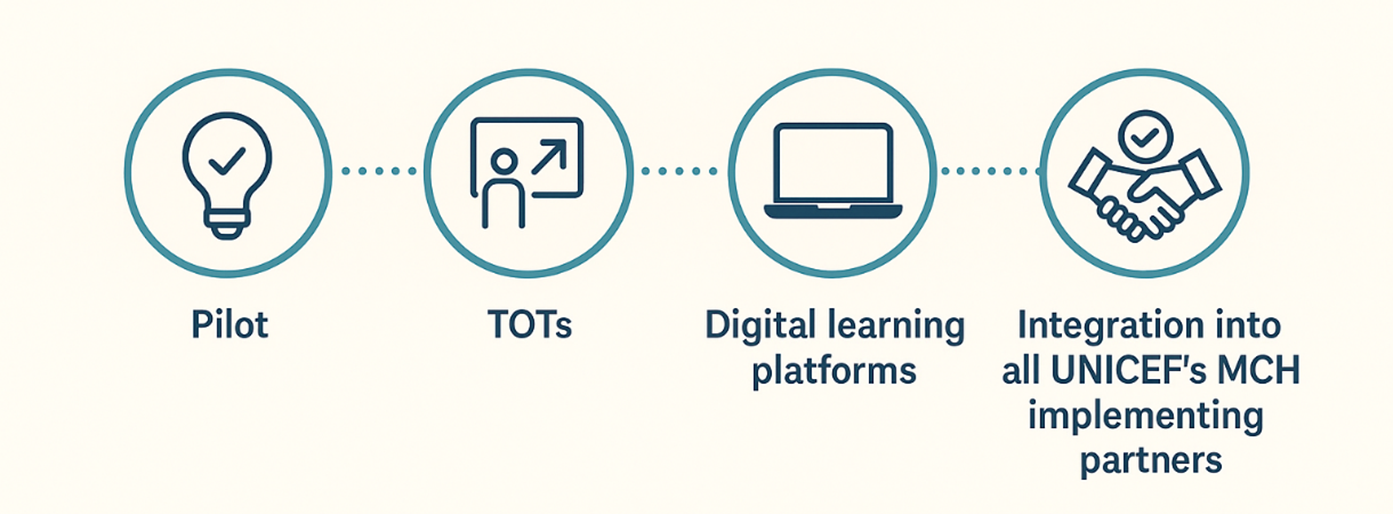

Steps of PMH implementation.

From pilot to scale: PATH’s approach to PMH

PATH’s work on PMH in Myanmar has evolved from a foundational pilot program to systemic integration.

Initial pilot activities demonstrated the feasibility of identifying and addressing PMH needs within routine maternal care. For the pilot program, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) screening tool was translated from English into Burmese.

Although a small pilot had previously been conducted in Myanmar, it was limited to peri-urban and urban settings. Therefore, this pilot screening was carried out in the Magway region, which is a conflict-affected rural area, to assess its feasibility and community acceptability. Following this, full implementation has been initiated.

Building on this evidence, training-of-trainers (TOT) sessions have equipped health care providers and partner organizations with essential skills with more sessions planned to expand reach.

The TOT sessions covered the following topics: mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS); perinatal mental health (PMH); common mental health problems during the perinatal period; triggering and preventive factors of PMH, integration of PMH into MCH activities, the Step care approach for PMH; management and referral pathways; skills for providing PMH support; provision of care for women with special needs, and the use of screening tools, such as the EPDS.

Techniques for pregnant and lactating women to prevent PMH such as thinking healthy, self-care, stress management, and building resilience are also introduced. In addition, role-plays and case scenarios are conducted to help participants apply the concepts to real-life situations. The practical use of information, education, and communication (IEC) materials is also taught, including discussions on the pros and cons of each IEC tool based on factors such as resources, reach, convenience, durability, mobility, and cost.

This capacity-building has yielded tangible results. From November 2023 to August 2025, PATH’s initiative successfully integrated perinatal mental health care into frontline services, equipping non-specialist providers to support vulnerable mothers. During this period, 1,423 women were identified and managed for perinatal mental health conditions directly within their communities, demonstrating the reach and effectiveness of the decentralized model. Of these, 81 women with more severe needs were successfully referred for specialist care, underscoring the program's role in ensuring a stepped-care approach that bridges community health workers with specialized services.

The next phase focuses on innovation and scale: digital learning platforms are in development to make training more accessible online and offline for those in the remote area with no or limited internet access, while active collaboration with UNICEF ensures PMH integration across all MCH implementing partners. Each step reflects a commitment to sustainable systems change, moving from isolated interventions to lasting transformation.

Toward a future where no mother suffers in silence

While progress has been made, sustained investment and collaboration are needed to ensure no mother is left behind. Critical gaps remain in workforce capacity, digital infrastructure, and community awareness. By aligning resources with Myanmar’s specific needs, the global health community can help turn isolated successes into universal standards of care—where every maternal health interaction considers both physical and mental well-being.

Mental health care isn’t a luxury, it’s survival. And for Myanmar’s mothers, the time is NOW.