Co-creating an improved response to postpartum hemorrhage

Every year, tens of thousands of women die from postpartum hemorrhage (excessive bleeding after childbirth). To stop these preventable deaths, PATH is engaging health system stakeholders at every level in the co-creation of appropriate and sustainable solutions.

Global leadership in maternal health.

Local expertise in human-centered design.

Deep relationships with Kenya Ministry of Health and county leadership.

Commitment to engaging health workers.

At PATH's Living Lab in Nairobi, Kenya, participants at a human-centered design workshop create an empathy map charting what a health worker thinks, sees, says, hears, and does in their work environment. Photo: PATH/Faith Mbai.

The challenge

Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is still the world's leading direct cause of maternal death—even though it is both preventable and treatable. It is so common that, in 2016, more than 225 women died of PPH every single day.

Of course, no two clinics or health systems are exactly the same, but common issues behind these PPH deaths include inconsistent protocols, inadequate staffing and resources, difficulty maintaining cold chain storage for medications, and poor emergency referral systems.

“Women are still dying preventable deaths. We must find ways to do more.”— Dr. Stephen Kaliti, head of reproductive and maternal health, Kenya

The solution

Health workers face these issues every day but are rarely asked to help co-create solutions—whether in the form of medical interventions, health policies, or action plans.

PATH's Living Labs Initiative uses human-centered design to accelerate the pace of health innovation by directly engaging end users—in this case, health system stakeholders including nurses, doctors, and health officials—in the rapid designing, testing, and scaling of solutions.

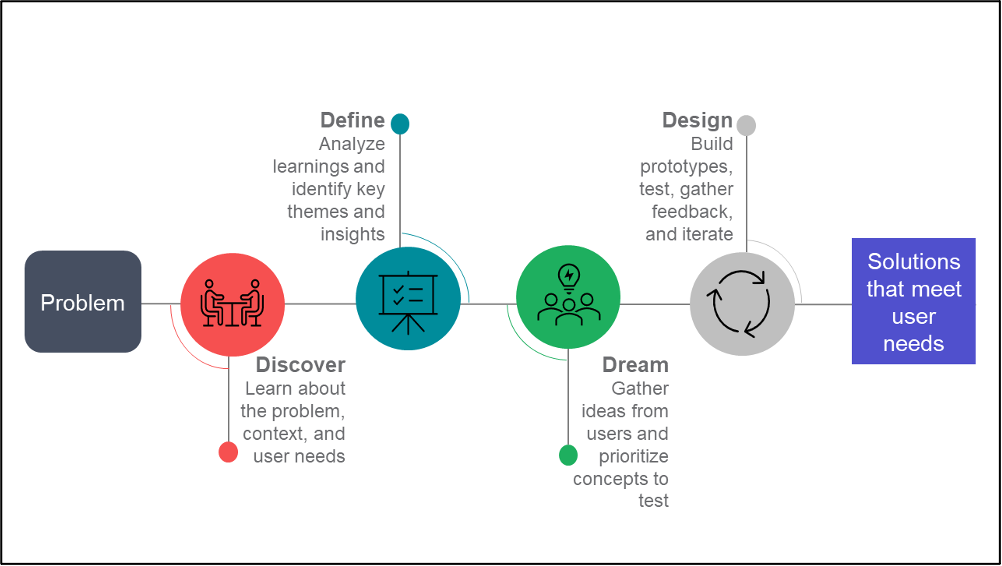

PATH’s Living Labs Initiative use a “4D” approach to human-centered design: discover, define, dream, design. At the design stage, rapid iteration continues until a solution is reached that satisfies end users. Illustration: PATH.

Human-centered design enables co-creation of solutions according to end-user needs. It's what PATH has always done and what our Living Labs Initiative continues to refine.

For example, PATH engaged frontline health workers and other maternal stakeholders in Kenya in a series of human-centered design workshops.

Together, we are now developing a deeper understanding of the barriers and opportunities associated with the prevention and management of postpartum hemorrhage in Kenya.

Why was PATH chosen to do this work?

The Living Labs Initiative draws on PATH's 40+ year history of collaborating with local stakeholders and designing appropriate health solutions. The following factors made PATH the perfect partner to engage in this work:

- Global thought leaders.

PATH staff are widely regarded as thought leaders in designing, introducing, and scaling innovations for maternal, newborn, and child health. - Local design and health system expertise.

Our in-country staff are human-centered design experts and have a deep knowledge of the local health systems, its challenges, and its opportunities. - Extensive in-country reach.

PATH is a trusted partner to the Kenya Ministry of Health and has strong relationships with health facilities throughout the country. - Commitment to partnering with health workers.

PATH is committed to deeply engaging with individuals to understand their challenges and to co-creating solutions that meet their needs.

Sue Wairimu, a Living Labs designer, interviews Triza, a nurse-in-charge at Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching & Referral Hospital in Kisumu, Kenya. These interviews—conducted prior to COVID-19—have highlighted common challenges. Photo: PATH/Faith Mbai.

Our approach

So how do we do it? We use human-centered design methods to immerse ourselves in the lives of health workers and build deep empathy for their needs. Then we analyze hundreds of their stories and ideas and turn them into action plans for saving mothers' lives.

In Kenya, we divided our approach into four phases.

Phase 1

We conducted a national workshop to gain an initial understanding of the problem from a range of health system stakeholders. This can be thought of as landscaping the challenges and identifying key roles and processes.

Phase 2

We hosted human-centered design workshops where stakeholders at all levels shared their stories, described how processes currently work, highlighted key challenges, and brainstormed potential solutions.

Storytelling is a key component of these workshops because it makes space for "outlier" perspectives and allows for a deeper understanding of the emotional struggle nurses face when mothers die from PPH.

“One person can't provide quality care to so many patients. Extra help is needed to ease the workload."”— Dr. Rosebellah Amihanda, Kisumu, Kenya

Phase 3

The Living Labs team interviewed staff from more than 40 health facilities. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Living Labs staff visited facilities in person to observe the processes and challenges described in the workshops. Following the start of the pandemic, interviews were conducted virtually.

Using the data and stories collected in phases 2 and 3, the Living Labs team created journey maps—step-by-step descriptions of everything that happens to a patient from admission to discharge. These maps allowed health workers and designers to identify clear goals, possible actions, and areas for improvement at each stage of care.

We then shared these stories and maps and experiences on a virtual whiteboard called Miro, which allows for collaborative analysis and identifying common themes across stories, clinics, and systems.

Phase 4

In the final phase—yet to be completed—stakeholders will be reconvened to review the results of workshops, interviews, and observations in order to determine which interventions should be included in a national costed road map.

The Kenya Ministry of Health will then use that road map to implement system-wide improvements and reduce maternal deaths from postpartum hemorrhage.

Lillian, a nurse-midwife at Mashambani health facility in Kisumu, Kenya. Results from this project will help counties implement action plans to reduce maternal deaths from postpartum hemorrhage. Photo: PATH/ Nelson Cheruiyot.

The results

Our human-centered approach generates huge volumes of qualitative data for analysis.

So far in Kenya, we've found the most common barriers to the successful prevention, management, and treatment of PPH include:

- Challenges maintaining the cold chain for medications that lose their potency when exposed to heat, light, and humidity.

- Inconsistent drug administration protocols in different facilities brought about by difference in drug effectiveness per dose.

- Under-staffed and under-resourced health facilities, including lack of pharmaceuticals for PPH prevention and management, as well as blood and blood products for transfusions in severe cases of PPH.

- Mothers receiving disrespectful maternity care, such as care providers dismissing their concerns.

- Absence of an adequately resourced or protocoled emergency referral systems, including a lack of ambulances and paramedics.

- Insufficient practical training and mentorship for health workers on management of PPH.

Some possible interventions that have been identified to address these challenges include:

- Training for health care workers on early identification, anticipation, and prevention of PPH.

- Strengthening the emergency referral system by increasing health care worker knowledge of protocols for referring patients and for providing clear and precise documentation during the referral process.

- Increasing supplies of alternative drugs for prevention and management of PPH.

“We need to look at all aspects of PPH and have mentorship on different modes of managing complications.”— Lillian, nurse-midwife, Mashambani health facility, Kenya

The qualitative data that informed these findings are now being disaggregated by county and paired for analysis with quantitative data using Kenya's DHIS2 health information system.

The ability to analyze qualitative and quantitative data together will give the Ministry of Health critical insight into why statistics and health outcomes vary from county to county. And those insights will inform next steps for clinics, the Ministry, and our local partner, Smiles for Mothers, who will carry this work forward.

Funding

This program is supported by funding from Merck & Co., Inc., through MSD for Mothers—the company's $500 million initiative to help create a world where no woman has to die while giving life.